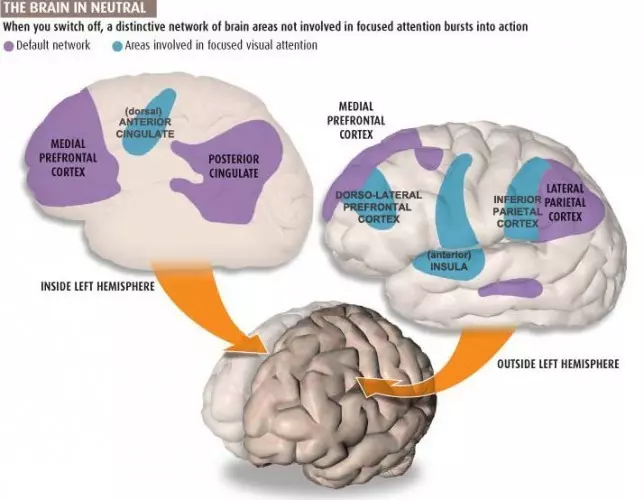

When we stop focusing on the outside world, the brain doesn’t shut down, it switches modes. In the absence of directed tasks or external stimuli, a different system comes online: the Default Mode Network (DMN). Often misunderstood as a passive state, the DMN is in fact one of the most metabolically active systems in the brain, and increasingly it is being linked to the psychological value of spending time in silence, solitude and stillness.

The Default Mode Network is associated with introspection, memory consolidation, imagination and self-awareness. It is active when the mind is at rest but awake; during daydreaming, reflection and undisturbed thought. In everyday life, these moments are rare. Most of our environments are designed for doing: attending, producing, responding. But the DMN thrives in the spaces in between, when we are unoccupied, undistracted and alone with our thoughts.

Recent studies have shown that time in quiet environments, especially those low in sensory input, enhances DMN activity. Unlike the attentional networks that dominate in task-focused settings, the DMN benefits from environments that allow withdrawal. This doesn’t require total isolation, but it does require spatial cues that permit mental wandering: soft acoustics, minimal visual complexitya and low social expectation.

In this way, the DMN is not just a neurological curiosity, it’s an architectural concern. Because how and where we rest shapes the kind of rest we receive. A room filled with notifications, background noise or open visibility does not support cognitive replenishment. A space that allows stillness and perceptual quiet does.

The implications are wide-reaching. In healthcare, design strategies that support DMN engagement are linked to improved emotional regulation and mental recovery. In education, they may support deep learning and reflection. Even in the workplace, moments of cognitive drift are associated with creative problem-solving. Yet in most built environments, silence is treated as a lack - something to be filled - rather than a function in its own right.

Solitude, too, plays a role. The DMN is deeply entangled with the sense of self. When we are alone, especially in still environments, the mind turns inward: evaluating, resolving, imagining. These are not inefficiencies. They are part of the brain’s baseline functioning, and the conditions that allow for them are spatial as much as they are temporal.

Stillness, then, is not about doing nothing. It is a mode of cognition that our culture, and our built environment, often overlooks. As we learn more about the rhythms of the resting mind, it becomes clear that design has a role to play in supporting them.