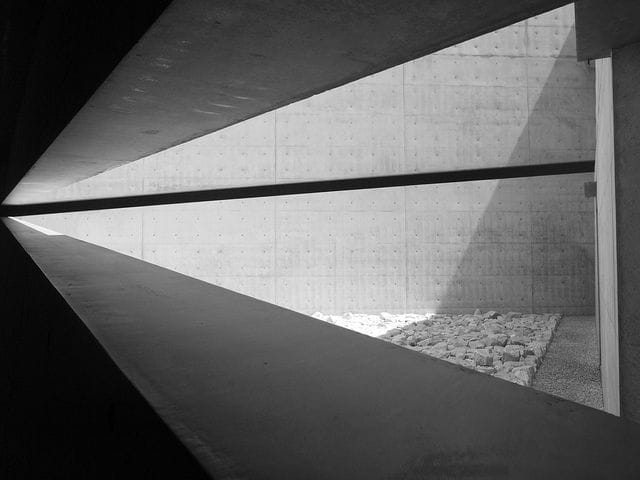

Silence has become rare. Not by accident, but by design. Our cities, buildings, and homes have been shaped around productivity and interaction, not pause. In a culture saturated with sound and visual noise, the absence of both is often read as absence of value. And yet, the desire for silence is increasing. Not as escape, but as necessity.

Silence is not the same as an acoustically dead environment. A room lined with insulation may be quiet in decibels but can still feel sterile, even disorienting. Silence in architecture is not defined by the removal of sound alone, but by how space receives it. It is less about muting and more about modulation. How a space absorbs, reflects, and holds sound can determine whether that silence is perceived as comforting or cold, restorative or empty.

The design of such silence is subtle. It is shaped through scale, texture, light, and proportion. Small rooms can become claustrophobic. Oversized spaces may feel detached or oppressive. A well-calibrated room—a ceiling not too high, surfaces that soften reverberation, daylight that arrives without glare—can create an acoustic and atmospheric balance that supports mental quiet.

These spaces are not inert. They are active participants in how we think and feel. Silence in architecture has the capacity to slow time, sharpen perception, and restore attention. In public life, this is more than luxury—it is public health. Retreat does not have to mean isolation. It can mean returning to something elemental: a clearer mind, a recalibrated body, a moment that belongs to itself.

We are not simply building structures. We are shaping how people experience space and, through it, themselves. Amidst the overstimulation of modern life, architecture must take seriously its role in designing silence. Not as emptiness, but as presence.