In a world saturated with noise, both physical and cognitive, spaces of stillness are becoming essential sanctuaries for the modern mind. But what makes an environment truly still? How can architecture guide perception toward a state of rest rather than stimulation? These questions find resonance in the work of Dutch architect and Benedictine monk Hans van der Laan, whose book Instruments of Thought presents a rigorous approach to architectural space that is deeply aligned with the principles of cognitive restoration.

At the heart of van der Laan’s philosophy is the idea that architecture is not just the creation of physical form, but an instrument for structuring human thought. His work challenges the conventional view of design as merely aesthetic or functional, arguing instead that spatial relationships such as proportion, rhythm, and hierarchy, shape perception in profound ways. When designed with intention, space becomes more than a container for activity; it becomes a framework for mental clarity, a filter for overstimulation, and a guide toward stillness.

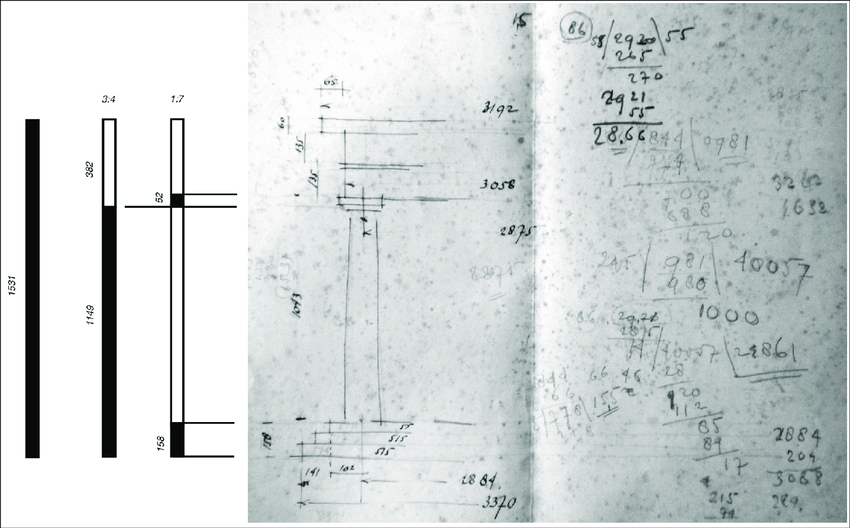

One of his key contributions is the plastic number, a proportional system that offers an alternative to the golden ratio. Unlike purely aesthetic theories, this system is rooted in how humans perceive space, creating an innate sense of balance and harmony. In environments designed for stillness, proportion is more than a visual concern—it is a cognitive tool. When spatial relationships are intuitively structured, they reduce mental friction, allowing the mind to settle rather than unconsciously work to process disorder. This is why some spaces feel effortlessly calming while others create a vague sense of unease; the way elements relate to one another shapes our perception on a subconscious level.

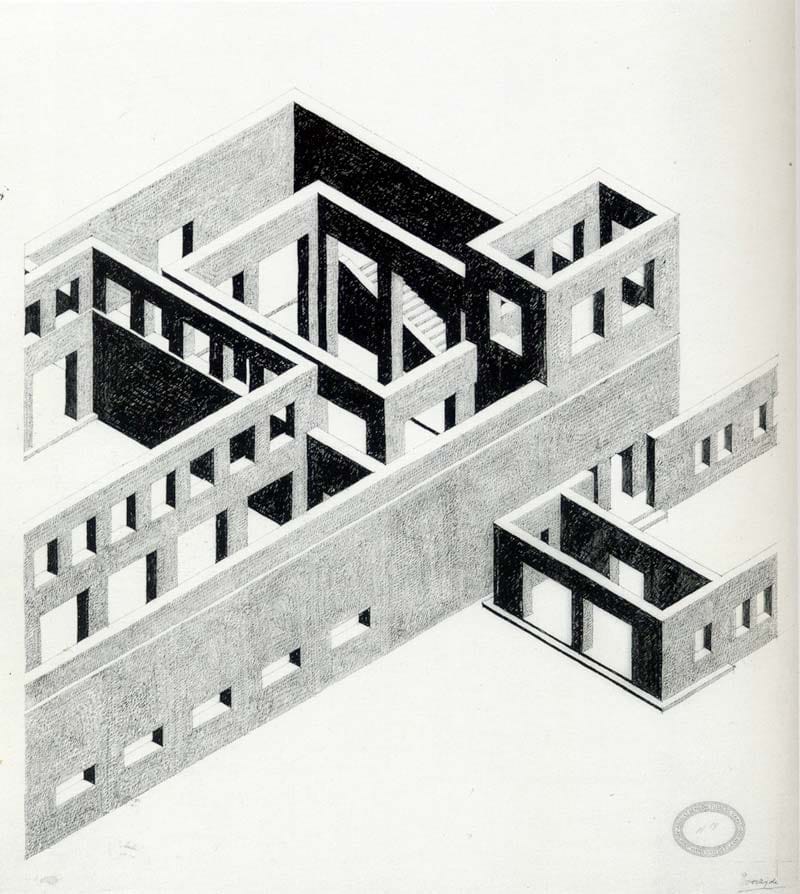

Beyond proportion, van der Laan also emphasized hierarchy in architectural composition. Just as clarity in thought comes from structured reasoning, clarity in space emerges from an intentional arrangement of volumes, thresholds, and spatial sequences. Spaces of stillness benefit from a hierarchy that guides movement and perception, allowing for retreat without isolation and openness without exposure. The transition from one space to another, the interplay of large and small volumes, the rhythm of enclosures and voids—all of these elements influence how a space is experienced on a cognitive level. In monastic architecture, where van der Laan’s ideas are most profoundly expressed, spatial progressions are carefully composed to shift perception from the external world to an internal state of contemplation.

Architecture, at its core, is a mediator between the mind and its surroundings. Van der Laan saw it as a filter, shaping how individuals engage with space in ways that either amplify or reduce cognitive load. The right balance of materiality, scale, and enclosure ensures that a space does not demand excessive mental effort, allowing the brain to disengage from unnecessary distractions. Designing for stillness is not about the absence of sensory input, but about the careful orchestration of proportion, order, and rhythm to create environments that support rather than overwhelm.

His ideas offer a compelling framework for a new kind of architecture—one that moves beyond visual trends and instead focuses on the deeper impact of space on human cognition. In a time when overstimulation is constant, the need for environments that offer respite is more critical than ever. Whether in hospitality, workplaces, or public spaces, designing for stillness means designing for a fundamental human need: the ability to retreat, recalibrate, and reconnect with a quieter state of mind. Architecture has the power to facilitate this, not through excess, but through the profound simplicity of well-ordered space.